To be confused with the horsemen on the other side of the Andes, the Chilean gaucho is, essentially, the same person. International borders may mean something to someone but the gauchos cross boundaries with the same ease (albeit sometimes across precarious mountain passes) as crossing a threshold into another bedroom. The geographical area known as Patagonia--whose somewhat arbitrary frontiers are also open to debate--is the native home of the gaucho, an area that occupies nearly a third of the total landmass of the two countries that employ the word.

In effect, the gaucho is a resident of a region rather than a country, a region defined by the featureless steppes (pampas) on the east side, to the lakes and high peaks of the Andean cordillera, and the fjords and impenetrable forests of the western side. The gaucho knows it all and the intimate knowledge of the landscape is reflected in everyday expressions and traditions.

Though more commonly associated with the cowboys of the South American grasslands in Argentina and Uruguay, guacho is, in fact, the correct term for the Southern Chilean cowboy as well. Huaso is the term of choice but the name is more correctly tied to the noble horseman of the Central Zone (the valleys surrounding Santiago) than the working class laborer of Patagonia. In terms of expressive culture and folklife, there are few similarities.

An equivalent might be the Mexican vaquero and charro. The charro, a descendant of the Spanish province of Salamanca came to the new land with the first conquerors. The charros were known as excellent horsemen and many were hired by the new Mexican government to patrol vast stretches of the northern deserts.

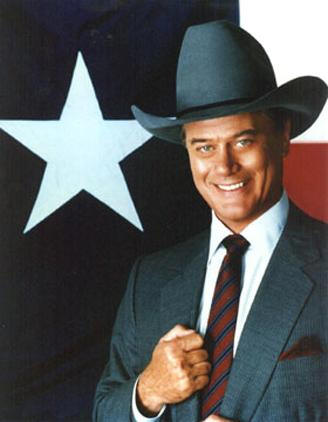

An equivalent might be the Mexican vaquero and charro. The charro, a descendant of the Spanish province of Salamanca came to the new land with the first conquerors. The charros were known as excellent horsemen and many were hired by the new Mexican government to patrol vast stretches of the northern deserts. The vaquero, then, was the product of an expanding cattle industry that pushed as far north as present day Montana. Though equally skilled, the vaquero's ancestry was often a mixture of Spanish and indigenous Indian blood. As the industry expanded, the distinction between the two grew as well. One worked with the livestock, the other owned the livestock. In other words, more ranch hand, less J.R. Ewing.

The vaquero, then, was the product of an expanding cattle industry that pushed as far north as present day Montana. Though equally skilled, the vaquero's ancestry was often a mixture of Spanish and indigenous Indian blood. As the industry expanded, the distinction between the two grew as well. One worked with the livestock, the other owned the livestock. In other words, more ranch hand, less J.R. Ewing.And so it goes in Chile, too, that you're likely to recognize the well-dressed weekend huaso who participates in the highly formal and stylized rodeos of the September 18th, Independence Day celebrations as the same businessman driving his Audi downtown Santiago the following Monday morning. The toy saddle dangling from the rear view mirror within the car may help you distinguish him; and the countryside disappearing from sight of the rear view mirror may hint at the social position of the Chilean huaso.

But it's different in Patagonia.

Most gauchos don't have the option of returning to the city for the work week to make their real living. Gauchos are gauchos and if they're not gauchos they're arrieros who make a living packing animals and transporting goods. In either case, they live their lives on the backs of beasts.

Their lives are a reflection of their work and their work reflects their lives. Everything is an amalgamation of their mixed ancestry, the varied topography, and the demands of the weather. Then there is mate but perhaps that's better left to another entry.

Argentino o chileno, no importa. Es todo lo mismo.

Some gaucho music from the west side:

Carlos Bello: Ovejero.mp3

Carlos Bello: Soy del sur.mp3

And one from the east:

Argentino Luna: El malevo.mp3

(Thanks, Michelle, for the music!)

All images are borrowed from someplace else. Please visit their sites:

Erin Simons Photography

Ciudad de Coyhaique homepage

Autry National Center of the American West

Olaf Wieghorst paintings

E-Verse Radio

KAWIN Ecotourismo

Trekking Chile

1 comment:

A very nice entry. This definitely supports my life's thesis: Patagonia is a nation.

To have shared some of these things in my research paper (which I already have with me) and see you have taken them into account makes me glad. Being difficult to understand if you haven't gone there, I can say this perfectly fits with the image people have of their own culture and the sense of belonging in Patagonia.

And by the way, I feel more patagonian rather than chilean.

Gracias :)

Post a Comment