31 August 2011

On the Road to Find Out 3

(Continued from Part 2.)

With only a few days to spare after returning from Lucca, the family--this time the whole family including Hazel Dickens and Annabelle Lee--hit the road again. The itinerary was short and fast and would eventually turn a bit intense. We were to drive to Luzern and overnight with our long-time friends Monika and Christen. From there we would take the train to Engelberg, the bus to the Luftseilbahn that would take us up to the Fürenalp. From the Fürenalp we'd hike a few hours up valley and stay overnight at the Blackenalp. The next day we would continue up the valley and cross the Surenenpass which would take us along a lengthy ridgeline to the enclave of Brüsti. From there, natürlich, we would take a cable car back down to Attinghausen, bus into Altdorf, and then take a train back to Luzern. Kein problem! Genau.

Saturday was perfect. The day pretty much summarized everything that you imagine as Switzerland: blue skies, a few puffy white clouds, green alpine pastures and valleys, melting glaciers, blonde children, happy dogs. Fresh milk. That sort of thing.

For the most part the day progressed as planned. We were excited for Hank who, though he has been hiking for a few years now, hasn't been on an overnight backpacking trip, albeit a backpacking trip without much in your backpack as well as the benefit of a roof over your head, full meals, and a bar waiting for you at the end of the day. We meandered, stopped for a picnic, and spent the first day at a leisurely pace.

At about the halfway point we heard a kind of scream, a maniacal yell of sorts, that finally and completely took our minds and bodies off the busy streets of Luzern, away from the hordes of tourists in Engelberg, and even far from the beer-drinking, sausage-eating crowds who would venture no farther than the restaurant at the top of the Fürenalp. The maniacal yell sounded something like this and was followed by the sound of a giant zipper opening above our heads and for the next 36 hours or so contemporary Switzerland would remain 3,000 feet and at least a hundred years below us.

What sounds totally bizarre in fact is totally bizarre but is also an example of traditional Swiss alpine customs and practices still in action. Turning our heads upward revealed the source of the zip noise: a long cable rising about 1,000 feet from a grassy knoll to a higher, less accessible notch of a pasture at the top of a cliff band. Hovering above us, riding the cable down to the knoll, was a hand cut bale of hay. The maniacal yell was a fairly typical call of an alpine herdsman used, in this case, as a warning that a new hay bale was being released from above.

Another two hours brought us to our destination for the night: the Blackenalp. An alp is a remote working farm used primarily in the summer by a herdsman and his helpers. It also doubles and triples as an inn for trekkers as well as a place to find a hot meal and a cold drink. Included with the price of a bed is dinner and breakfast the following morning. Switzerland and the rest of the Alpine countries are so dotted with these inns, chalets, huts, and/or refuges that it's possible to link up an entire summer of crossing up and over high altitude passes and country borders without ever dropping down into the valleys to stock up on supplies. It's a great way to experience the (semi) solitude of backpacking without packing quite as much stuff on your back.

The Blackenalp consists of a barn equipped with milking stalls--used twice daily--a main building with upstairs room for maybe thirty travelers, a large dining room, large kitchen and workspace for cheese and butter production, and a partially buried cellar for all things dairy. Separated from the main buildings on a grassy knoll is a small chapel (room for twelve) whose bells are rung every night as a show of appreciation for the day's work.

The smell of rich, grassy milk permeates the Blackenalp and, indeed, is the reason for its existence. Though the herdsman watches over a total of about 500 head of livestock, split between cows and calves, steers, and sheep, the profits from milk, cheese, and butter go straight into the his pocket. Income is also generated through money collected from trekkers for room and board and additional sales of food and drink. The bulk of the herdsman's income, however, is paid to him by a local cooperative of livestock owners who hire him to tend their animals for the summer. The Blackenalp itself is under the ownership of the cooperative who, in turn, lease their high valley pastures from the State. Not a money-making proposition--at least for the herdsman and his assistants--but this is also why so many traditional customs, practices, and rituals still persist.

For example, there are few things more traditional than the food the alpine herdsmen eat and for our night's stay at the Blackenalp we were treated to the most traditional of traditional meals: Älplermagronen and fresh Apfelmus!

What else could a person who is surrounded by fresh, flowing milk afford to eat and feed his help that wouldn't significantly cut into his profits? Pasta, potatoes, onions, cheese, butter, and sour cream, of course. Smash a whole bunch of apples that were hauled up on the last supply run and you've got yourself a meal that will fill the belly and knock you down for the night. Wake before dawn, eat a bunch of fresh cheese, butter, and warm bread, wash it down with instant coffee and head out on your four-hour romp around the entire valley to check the livestock. Return to milk the morning cows, work on projects around the property for the afternoon, then leave again for a second four-hour trip around the valley. As soon as the second check is completed the evening cows need milked. At dusk the Älplermagronen and Apfelmus is placed on the dinner table, devoured, and followed by more instant coffee and a glass or two of schnapps. The day's work is done; the life of a Swiss herdsman is a series of ancient rituals.

The next morning we said goodbye to the Blackenalp under cooler temperatures and a changing sky. Within a half-hour a light mist fell and it appeared that we wandered out of Switzerland and straight into the Scottish Highlands.

For the rest of the day the clouds and rain would not lift and would only grow in intensity once we crossed over the Surenenpass and walked toward Brüsti. Pretty, but with a seven year-old to keep happy and positive, constant rain quickly loses its appeal.

Two hours of climbing took us to the Surenenpass. It was here, less than halfway through the day, when the skies opened up in earnest. We took a quick break in the Schutzhütte before launching into another three hours of non-stop rain.

I kept the Lovin' Spoonful on a constant loop in my head. This helped keep the bad spirits away. But it wasn't me I was worried about. Hank did well going down off the pass and even for a while on the long ridgeline to the Brüsti. Five hours of walking in the rain is a lot to ask of a seven year-old--hell, it's a lot to ask of a 42 year-old. Without a tree in sight, without any more huts to take shelter for a while, moods inevitably deteriorate. And they did. And it was difficult.

Persevere he did and eventually we made it to Brüsti and the Berggasthaus Z'graggen was open and the tears stopped falling. Henry drank the two best hot chocolates of his life, his parents and friends drank eight or so Kaffee fertigs (coffee and schnapps), and we rested an hour before the cable car took us back to the lowlands.

In Altdorf we waited for a bus (in the rain) in the city's main plaza. Altdorf is home to the great Swiss patriot and assassin, William Tell. William the brave. William the bold. William the expert marksman. William who broke the rules and was forced to shoot an apple off his son's head for doing so. He did (natürlich!) and was sent to jail for his feat. In a storm on Lake Lucerne he escaped his captors and returned to assassinate the tyrannical Austrian overlord, Albrect Gessler. William's defiance and bravery started a rebellion in the Canton of Uri that eventually led to the formation of the Swiss Confederation. Pretty dramatic stuff though a distant memory from the quiet as a mouse, passively aggressive Switzerland of today.

As is the case with any good legend, the legend of William Tell doesn't quite match the history records. William Tell could have been a real person; he also could have been an amalgamation of several people. The William Tell legend belongs to a group of mostly German, Scandinavian, Danish, English, and even Balkan folk legends that the folklorist Stith Thompson gathered together in the famous Motif Index under the title "Skilful marksman shoots apple from man's head." What this means is that legends with different characters and place names but similar in that they all contain the "apple-shot" motif had been circulating orally for hundreds of years before surfacing in central Switzerland with William Tell as the hero and the Austrian Habsburg overlord as the villain.

Does that mean that William Tell didn't exist? No. Does that mean that he didn't perform the actions according to the legend? No. What it usually means is that over time, starting in the mid-15th century, at least some if not all of the storyline has been altered or modified to meet the cultural, political, and social values of the Swiss citizens. The fact that a statue stands in the middle of Altdorf and stories continue to circulate demonstrates that the legend of William Tell is still a narrative depiction of Swiss values and effects the way the Swiss view themselves in relation to others.

No matter. At five o'clock on a Sunday evening, soaked to the bone and with the rain still falling, even I wasn't that interested in how a 500 year-old legend still determines the value system of a small European country. All we wanted was a warm shower, dry clothes, and a hot meal. In three hours time those tasks were complete. In five hours we were driving back to Geneva.

At some point along the way, Fred Neil played from a compilation CD I had in the stereo. The weather had cleared (natürlich) and in front of us the last brilliant sliver of bright orange hung on to the far western tops of the Jura Mountains. It was a bright, deep, rich orange, the kind of sunset that only appears after an all-day cleansing of the atmosphere. The rest of the family, including the dogs, had long since passed out and I was left alone to the end of a beautiful day and the voice of Fred Neil.

(Continue to Part 4.)

23 August 2011

On the Road to Find Out 2

(Continued from Part 1.)

Lucca. Lucca, Italy. Lucca, Italy is in Tuscany. Tuscany is pretty. Like most cities in Italy, Lucca is an old city. Lucca is also a walled city.

That's about all I knew about Lucca before dropping down that way and about all I know about Lucca now. But a two week flurry of activity passed after visiting the Beaujolais and I knew we needed a break. Two weeks of the end of school year busyness and, for me, the end of a job that should have been wrapped up a month earlier. The end of June culminated with a storm of schedules and commitments and obligations and I wanted none of it, so in a period of about 36 hours the decision was made, an apartment rented, the car packed, and Hank and I headed for Lucca.

Lucca was chosen almost randomly. Some friends of ours chose Lucca as a place to stay for a week after some sort of giant birthday bash they threw for each other up north in the Piedmont. The possibility of seeing friends, an apartment with a pool, and a New York Times article about how Lucca is the epicenter of Tuscan cuisine were enough reasons to fill the gas tank and go. And in a long and groggy blink of an eye we arrived.

Dad's tired feet and one happy swimmer:

With the first plunge out of the way we settled in on finding some Lucchese cuisine. Instead, we found pizza and a wine bar that served cold appetizers and wine from the tank. Close enough.

The food experiences continued positively but nothing like the Piedmont, Rome, or even meals I've had in the Aosta. With a seven year-old in tow I knew I couldn't expect too much; three-hour meals don't sit well with a boy who has difficulties giving a slice of pizza the time and focus it deserves.

I wanted to dedicate at least one lunch to eating well so using the New York Times article I chose La Mora, the best of the best. With map in hand, Hank and I drove out to Ponte a Moriano, a small commune about 15 kilometers from Lucca. The day was hot and when we arrived the town was deserted. I knew we were running late though still ahead of the two o'clock closing hour for lunch service. But the doors to La Mora were locked, the blinds drawn, and I feared we'd be eating the ubiquitous doner kebabs back in town. Luckily, just down the road from La Mora, the doors of the Antica Locanda di Sesto trattoria were still open. Lunch was saved.

The meal was excellent: house raviolis stuffed with truffles and walnuts; marinated anchovies with white beans; sheep's milk cheeses from the region; even Hank's spaghetti pomodoro was "the best ever!" The family run trattoria operates within a building that dates back to 1368. In addition to the restaurant, the Barattini family makes their own olive oil, small batches of wine, sheep's milk cheese, and cured meats. Plus, they couldn't be friendlier.

As for La Mora, its story is not as positive. I was informed that after a difficult period two years ago that saw several changes in chefs, the celebrated and beloved owner took his own life somewhere near the quiet river that flows close to town. Lamberto Barattini told me it was a shock and great tragedy for the entire community. La Mora will not reopen.

The following day, the proprietor of the villa, a stocky, handsome Sicilian, pointed out some deer grazing in a lower meadow. "Sometimes," he said, "you also see wild boar running through there."

"Wild boar," I said. "Those make for good eating."

"You like eating boar? Would you like to eat boar? I could make you a reservation at a restaurant very close to here. It is an honest place and not so expensive. You can eat wild boar."

An honest place. I wasn't totally sure what the Sicilian meant by that but I liked the idea. I also liked the idea of eating boar.

Later that day I was given a hand drawn map to the honest place. This consisted of two lines that formed an upside down 'y' on the page. The short end represented the road that led to the villa. At the intersection was an arrow that pointed off the page toward Lucca. The long side squiggled up the page and ended at a small box that read Mariano. This was the restaurant. The squiggly line signaled a drive up a winding road in the foothills until you saw the restaurant. "There is a sign along the road," said the Sicilian, "you can't miss it."

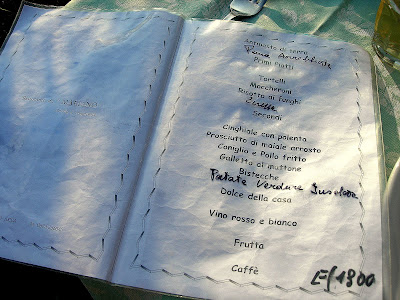

By a single squiggly line he meant a single road with many opportunities to take wrong turns at other junctions not represented on the map. By a sign he meant a small, hand-painted board tucked into some brush at a bend in the road that you could easily pass. By a restaurant he meant someone's backyard with enough altitude that it faced the other side of Lucca's hills toward Viareggio and the Mediterranean Sea. Perfect.

The light was blinding, the day's heat waning. At 7:30 pm we were only the second table but by the time we left at 10:00 the backyard was full.

The tables were the green plastic kind and off-kilter. The wine list consisted of a white and a red made somewhere on the hilltop and served in large carafes and heavy water glasses. The entrance to the kitchen was the back entrance to the house and doubled as a workspace for the garden. You could hear the dishwasher running and the conversations of the women inside while they cooked the night's meals and cleaned up afterwards. It was an honest place.

The food, like everything else, was sincere and generous. It will never compete for the one Michelin star left after the demise of La Mora but it will never pretend to, either. It was the kind of food you would expect to eat while relaxing in someone's backyard in the Tuscan foothills watching the sun go down on the Mediterranean. Probably most things were grown, raised, hunted, and foraged within close proximity to the restaurant. The tomatoes were some of the reddest and richest I've ever eaten. The limoncello was neon green from the fresh laurel, oregano, and sage infused into the drink. Everything reflected sunshine.

The next morning we found our only neighbors, a Dutch family who has spent the last seven years staying at the same villa for three weeks at a time. They had a son two years younger than Hank and a daughter of the same age. Thus began the summer love affair that included rescuing tiny frogs every morning that fell into the pool, shared art projects, and making do with different languages.

From the parents I learned more about the city in 30 minutes than I had the entire 36 hours of planning our vacation. For example, Lucca holds an outdoor Summer Music Festival every year in the center of the city. Yes, Martin thought, the festival should have started already. A quick search on his computer-phone-communicator thingy told us that, in fact, there was a concert the next day. Burt Bacharach. Would I like to go? The week was sealed.

I like Burt Bacharach's music. I didn't hesitate to buy tickets. I never thought about seeing Burt Bacharach live and, truth be told, I wouldn't have gone out of my way to see a show. He's a composer and not as well known as a performer. But of course we went. It was Burt Bacharach playing with a full band and three singers in the middle of an ancient Etruscan city. Yes, we went. No, they didn't allow cameras.

In short, Burt was great. Burt is old but his songs don't age. He started with a few medleys and I was worried for a Las Vegas-style revue. Then gears changed and the three vocalists--Josie James, John Pagano, and Donna Taylor--took turns fleshing out full songs. The vocalists then took a break while Burt and his band played a half-hour's worth of film music. The vocalists returned for another hour or so and an additional two encores. In total, Burt (I call him Burt) played for close to three hours, not bad for an 83 year-old.

There was a point toward the end of the concert when Burt played the piano and sang, without any other accompaniment, the sweetly philosophical "Alfie." Though his 83 year-old voice struggled in the higher register, the song, both music and lyrics, was delivered with wistful and delicate beauty. Sitting in Lucca's Piazza Napoleone under the clear, warm, July sky, with Hank falling asleep on my lap, I couldn't have imagined a better way to experience the relief of contentment.

(Continue to Part 3.)

18 August 2011

On the Road to Find Out 1

This is a tale of a summer. It was a summer of many travels with several different stages. Five stages, to be exact. The five staged summer was a summer of friends, a summer of family, a summer of solitude. It's been a cool summer and I'm grateful for that. It's been less stressful, less heartbreaking than last summer, and I'm grateful for that, too.

It's been a long, busy, and generally good summer. As always, it taught me about expectations, as in trying not to have them. Also, I've learned a lesson or two about spontaneity, as in act that way more often. Up, down, back, and forth, it's been the summer of the road more traveled.

It started in the Beaujolais, a wine region I never thought much about before moving within three hours of it. Then, thanks to Roy Cloud and his company Vintage '59, I tasted the 2005 Domaine du Pavillon de Chavannes Cuvée des Ambassades from the Côte de Brouilly and all my wrongs were righted. There was none of the sweet, candy-fruited juice that makes its way over to the American shores in the form of Beaujolais Nouveau or the mass marketed Georges Duboeuf wines. This was a wine borne from the limestone and granite soil it was raised in and the soft sunshine that presses down upon its hillsides. It's pretty, it's elegant, its tannins are fine and chalky. It's versatile with food and, as the six year-old bottle attested, it's able to age. My interest was piqued, appointments were made, and so began the summer.

Domaine du Pavillon de Chavannes couldn't see us so we made a cold call to another vigneron whose wines I've been digging: Clos de la Roilette located in the appellation of Fleurie.

Big, juicy, but fine tuned and earthy, these wines are excellent examples of the complexity of Gamay when left in the hands of an artist. Alain Coudert opened several bottles of the Clos cuvée (2007, 2009, 2010) two vintages of the Cuvée Tardive--a selected blend of old vines aged partially in oak foudres, or large casks--and an even smaller production and otherwise unavailable wine called the Griffe du Marquis, literally Claw of the Nobleman. The grapes for the Griffe du Marquis come from a single parcel, are aged in smaller casks, and exhibit an earthiness or sauvage more commonly seen in the big brother region to the north, Burgundy. Excellent, all.

Next we headed back to the Côte de Brouilly and the beautiful estate of Claude and Evelyne Geoffray at Château Thivin. Claude took us on a complete tour of the place before sitting us down at a table with bread, local chevre and sausage, and several vintages and different cuvées--the estate cuvée, Cuvée Zacharie, and Les Griottes de Brulhie.

More elegant, more pretty, and more structured than the wines of Clos de la Roilette, we probably should have tried the Thivin wines first. We still walked out of there with several cases under our arms (and a couple older vintage magnums!) and were ready to start the second part of the journey: the eats.

Night #1 took us to the decidedly uncrowded Les Platanes de Chénas in the village of Les Deschamps. Night #2 was spent at L'Atelier du Cuisinier in Villié-Morgon, a decidedly more crowded but no less delicious bistro where we dined on, among other things, bone marrow, snails, and frogs.

Walking and driving narrow country roads filled the rest of the trip. Not a moment was wasted. Technically, summer was still two weeks away when schools would empty and roads would fill. We jumped the gun a bit and were luckier for it. The villages were quiet with a looming air of anticipation. For the time being the Beaujolais felt like ours for the asking, which seems appropriate as it was a wine region I previously ignored. Not now and no more, however. We quietly slid away before the rest of the world descended.

(Continue to Part 2.)

13 August 2011

03 August 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)